The claim that heritage (understood as an integral concept that combines natural and cultural, material and immaterial) has importance in its relationship with people and not only as an object of worship is not new. Our society has evolved over time in terms of its interrelation with heritage, incorporating the criteria of cultural democracy having as a consequence, trends such as new museology, environmental education, mediation, and many other theories of heritage communication, including heritage interpretation (HI).

But what differentiates HI from other forms of heritage communication?

To answer this question, Freeman Tilden conducted a study on the effectiveness of visits offered by the United States National Park Service. Tilden set out to investigate whether they impacted the audiences or not. His goal was to research whether there were principles that allow us to connect with people both cognitively and emotionally. This work culminated in 1957 with the publication of the book “Interpreting Our Heritage” which laid the fundamentals for the communication of heritage leading not only to understanding but also to the appreciation for the place visited.

Let us then enter the answer to the initial question:

- HI is a kind of communication that requires very detailed planning.

- It is linked with social constructivism theories related to a collaborative approach. Tilden suggests that we must start from the experience and personality of the visitors to create new knowledge.

- In interpretation, the messages must be great truths, leading to the essence of heritage, so we do not serve the traditional exposition of information typical of more classical communication. We talk about revealing meanings, not only to provide some data.

- Creativity is fundamental in HI. Tilden (1957) says that “it is an art, which mixes many arts” addressed to reach our goal of communicating the soul of heritage.

- The backbone of HI is to achieve not only instruction but provocation, enhancing the importance of sensory and emotional communication to convey values. On the latter, David Uzzell (1989) proposes the notion of Hot Interpretation. “The term “hot” primarily refers to the use in interpretation of personal values, beliefs, memories, emotions, etc.: anything that elicits a degree of empathy and emotion from visitors (Uzzell and Ballantyne 2008) and is capable of creating processes of knowledge and behaviour. “Cold” interpretation would be that which proceeds directly to the components of knowledge, relegating emotions to the background (Navajas, 2020).

These ideas are reflected in the conclusions (Rodríguez, 2022) of the 21st Conference of the Asociación para la Interpretación del Patrimonio [Association for Heritage Interpretation], held in 2021, where participating professionals made the following proposals:

“Our heritage is not, and should never be, an objective act. On the contrary, interpreting heritage always entails conveying values and urging others to embrace conservation and social change.”

The mission of heritage interpretation

Nowadays, the conservation of heritage, in any of its multiple forms (natural, cultural, tangible or intangible), remains one of the most relevant missions of interpretation. With this in mind, interpretation professionals must continue working to provoke thought and promote processes of reflection and education. The goal is to generate positive attitudes and encourage the public to become active participants in heritage conservation.

Interpretation is also a tool for social transformation, helping to shape future citizens who are both critical and committed to the community and its values. In addition, interpretation is a valuable heritage management tool, as it creates spaces where people can interact (cognitively and emotionally) with their heritage, generating tourist, educational and social uses.

To conclude, we would like to highlight another of the ideas raised at that meeting (Rodríguez, 2022):

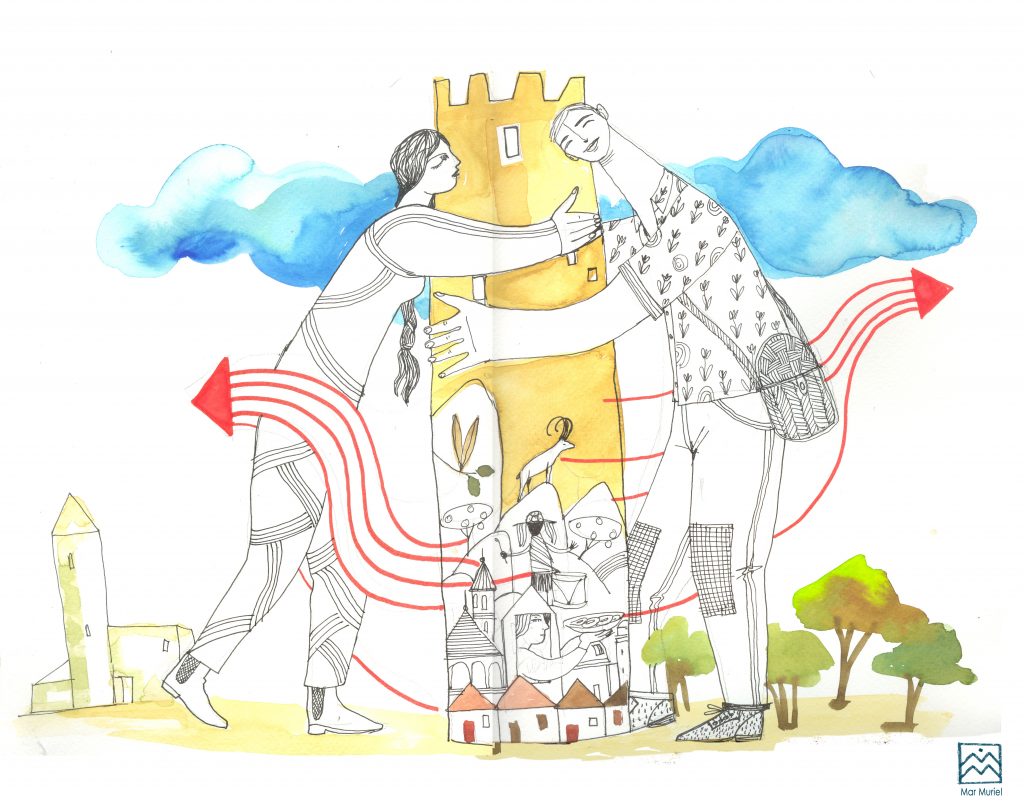

Interpretation has tremendous potential for building bridges with other heritage-related areas that share the same basic objectives, such as museology, cultural mediation, environmental and heritage education, sustainable tourism strategies, etc.

Disciplines that are strictly compartmentalised in academia must become porous in the professional world, as in practice they have similar principles, resources and purposes. The constant striving for professional success and recognition can often make us lose sight of our common ground, creating labels and names that differentiate and divide, but this separation isolates and impoverishes us all. We need to advocate for more permeable, porous disciplines and share our knowledge and tools for the greater good of society.

Maribel Rodríguez Achútegui and María Elvira Lezcano González

Association for Heritage Interpretation (Spain)